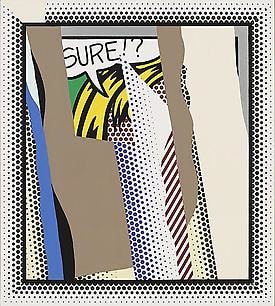

September 23, 2010 Following the Dots Around the City By ROBERTA SMITH Autumn in New York is the perfect time for an accidental festival of the work of the Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. This one is made possible by three separate exhibitions spread around Manhattan, which seems only fitting. After all (and perhaps surprisingly), Lichtenstein was one of the few great American painters of the postwar era born on the island of Manhattan: in 1923, into the cushier precincts of the Upper West Side. He attended public school and then the private Franklin School for Boys before heading off to Ohio State University to study painting. He died in Manhattan in 1997. Lichtenstein's art forms an ode to the Americana of comic books and commercial art, but it has about it a brisk cosmopolitanism that is also New York at its most New York, which is in the fall. The closest analogy may be musical: the songs of Broadway composers like Cole Porter, which radiate the energy of vernacular language being put in perfect working order. Perfect working order is what Lichtenstein was all about. And the loose-jointed survey of his economics afforded by these shows is all the more pleasant for being interrupted by large swaths of the city, which works pretty darned well in spite of everything. You can alternate views of Lichtenstein's genius with healthy intakes of urban life and draw your own conclusions from the shows' overlaps and discrepancies, whether with one another or reality. The most substantial effort is the Morgan Library & Museum's brilliant "Roy Lichtenstein: The Black-and-White Drawings, 1961-1968," which concentrates exclusively on the large finished drawings that heralded the arrival of his bold mature style. It is a high-octane affair suffused with the energy of an artist rapidly getting up to speed and reinventing drawing as he goes. A broader view is taken by "Roy Lichtenstein: Mostly Men" at the Leo Castelli Gallery on the Upper East Side. Its 25 works concentrate on depictions of men, skimming across a career more identified with anxious young women. And in Chelsea, Mitchell-Innes & Nash rounds out the bill with "Roy Lichtenstein Reflected," which features 10 paintings, mostly from the late 1980s and early '90s, that one way or another depict mirrors. While more routine it gets to the heart of Lichtenstein's concerns. As each show has its own catalog, a kind of Lichtenstein Festschrift also accrues. The Morgan is definitely the place to start. It brings a new clarity to Lichtenstein's evolution by focusing on the drawing materials and methods that made his beguiling advertising and comic-book images possible. It counters the anonymity of touch typically ascribed to his work by revealing the care, thought and effort that went into his ultracool look, which isn't so hands-off after all. Despite the 1961 of the title, the two earliest works here are from 1958, the year after Lichtenstein returned to the New York area after about 15 years away, during which time he served in the Army (1943-46), earned undergraduate and graduate degrees at Ohio State and also taught there. Like many artists his age in the 1950s, he was looking for a way around the histrionics, spontaneity and open-endedness of Abstract Expressionism. Contact with Allan Kaprow while both were teaching at Rutgers University especially helped sharpen his senses to the potential of everyday visual culture. The two 1958 works depict Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse in brush and ink amid tornadoes of Abstract Expressionist gesture. We see no more of the style until the end of the show, when Lichtenstein wryly honors it with cartoon depictions of swashbuckling brushstrokes against Benday-dot backgrounds. In between comes a parade of indelible no-nonsense objects and characters culled from American printed matter: comic-book fighter pilots in the heat of battle, Greek temples, sunsets, a hot dog, a ball of twine, a wide-eyed gas station attendant and a fabulous bathing beauty with piled curls and radial eyes. In these Lichtenstein rebuilds drawing from the ground up with a canny mix of commercial and fine-art techniques that accommodates a tremendous range of tones and textures. A crucial breakthrough, first evident at the Morgan in the seemingly heated "Conversation" of 1962, was the switch from wet to dry drawing mediums. Until graphite replaced brush or pen and ink, many of the drawings look too much like real commercial art: set to go to the printer and then be thrown out. Dry materials facilitated the pursuit of the Benday dots, intimated first by making graphite rubbings on window screen and then evoked more accurately by forcing lithographic rubbing crayon through a small sheet of metal, hand-drilled with rows of holes. (These tools and others are displayed in a vitrine.) Making dry versions of images originally drawn and then printed in ink, Lichtenstein altered their DNA, slowing them down into collagelike constructions that for all their boldness sustain old-masterish savoring. The artist's hand is everywhere, adjusting the density of the dots from faint to dark (sometimes by doubling them up), filling in areas so that even finer lines have a slightly chiseled, insistent roughness, and making useful discoveries. In "Bread and Jam" the gleam of the plate jumps out as something new. You can imagine Lichtenstein chuckling at the effect — fake image, real light. What is perhaps most striking is his determination to have the entire sheet of paper come alive and register as a whole. This electricity unifies nearly all his paintings, edge to edge, with a bracing combination of the familiar and the abstract that still has few equals in modern art. The Castelli show offers a change from the relative tunnel vision of the Morgan exhibition, branching out to include paintings and sculptures and the bonbonlike colored-pencil studies. (It incidentally complements "Roy Lichtenstein: Girls," a 2008 exhibition that was at the Gagosian Gallery around the corner.) Several works at Castelli are being shown for the first time in New York. "Indian," a small painting from 1951, when Lichtenstein was still in Ohio, reduces the male figure to a starlike tangle of points and angles that becomes a pictorial staple. A surrogate for both geometric abstraction and men, this form is often paired here with a sinuously Surrealist lock of blond hair and red lips. In "Indian," however, it is on its own, embellished with a few leaves or feathers and a pair of eyes. The work not only reflects careful attention to Picasso, but also presages Jasper Johns's splayed-face motifs from the late '80s, which were also inspired by Picasso. Other first-timers include two nearly identical paintings from 1961 of an image of a Sinatra-like playboy that could have been lifted from a matchbook cover. One is "Portrait of Allan Kaprow"; the other is "Portrait of Ivan Karp," after the art dealer who, as Leo Castelli's right-hand man, advocated that both Lichtenstein and Warhol be shown. They also bring to mind "Factum I" and its copy "Factum II" — two works with which Robert Rauschenberg sent up the deathless uniqueness of the Abstract Expressionist brushwork. Other works to seek out here include "The Conversation," a 1984 painted and patinated bronze sculpture of a Surrealist female head paired with a male head that is all right angles and exaggerated wood-grain, and a 1997 drawing that is unlike any work of his I've ever seen. It resembles one of Matisse's brush-and-ink nudes, except that it portrays a debonair young man in a suit. Moreover, its thick lines are charcoal, filled-in and a little rough — another wet-dry conversion that evokes his approach in the Morgan show. It signals a phase of late work that Lichtenstein, sadly, was unable to complete. "Roy Lichtenstein Reflected" at Mitchell-Innes & Nash does not achieve the curatorial density of the other two shows, but nearly every painting is a scintillating world unto itself, a bolt of Lichtenstein electricity. It is as if the gleam on the plate in "Bread and Jam" in the drawing at the Morgan had exploded into the mirror theme. The essential, slyly reflective nature of Lichtenstein's art is made palpable. He is always mirroring the world back to us, his own art included, as suggested here by two paintings in which his signature blonde all but disappears into shards and shafts of reflection. As such, the Mitchell-Innes ensemble forms a fantastic finale to the three shows, providing one view after another of a vernacular language fine-tuned to perfect working order. It's delovely.