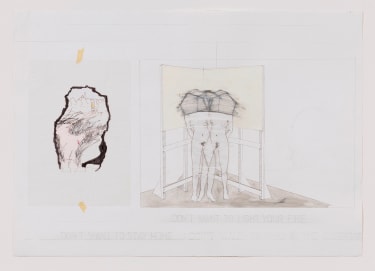

MONICA BONVICINI

Untitled (Hausfrau Swinging)

1997

Graphite, temper, ink, oil crayon, colored pencil, tape and tracing paper on Fabriano paper, collage

27 5/8 by 39 5/16 in. 70.2 by 99.9 cm.

(MI&N 13874)

Mitchell-Innes & Nash is pleased to present a selection of works dating from the latter half of the 20th century, addressing the vast social, political and technological changes of the period.

While the term "fin de siècle" is most often associated with the end of the 19th century, it has been applied to the 20th, especially with regard to parallel concerns and ambitions similarly precipitated by advances in both technology and industry. Realist but hopeful, the works in this OVR address how these changes both influenced traditional ways of seeing and opened up new perspectives on familiar subject matter.

On view in this online presentation are works by: Monica Bonvicini (b. 1965), Jay DeFeo (1929-1989), Nancy Graves (1939-1995), Kiki Kogelnik (1935-1997), Justine Kurland (b. 1969), Annette Lemieux (b. 1957) and Jessica Stockholder (b. 1959).

MONICA BONVICINI

MONICA BONVICINI

Untitled (Hausfrau Swinging)

1997

Graphite, temper, ink, oil crayon, colored pencil, tape and tracing paper on Fabriano paper, collage

27 5/8 by 39 5/16 in. 70.2 by 99.9 cm.

(MI&N 13874)

MARCEL DUCHAMP

Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas) (1946-66)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

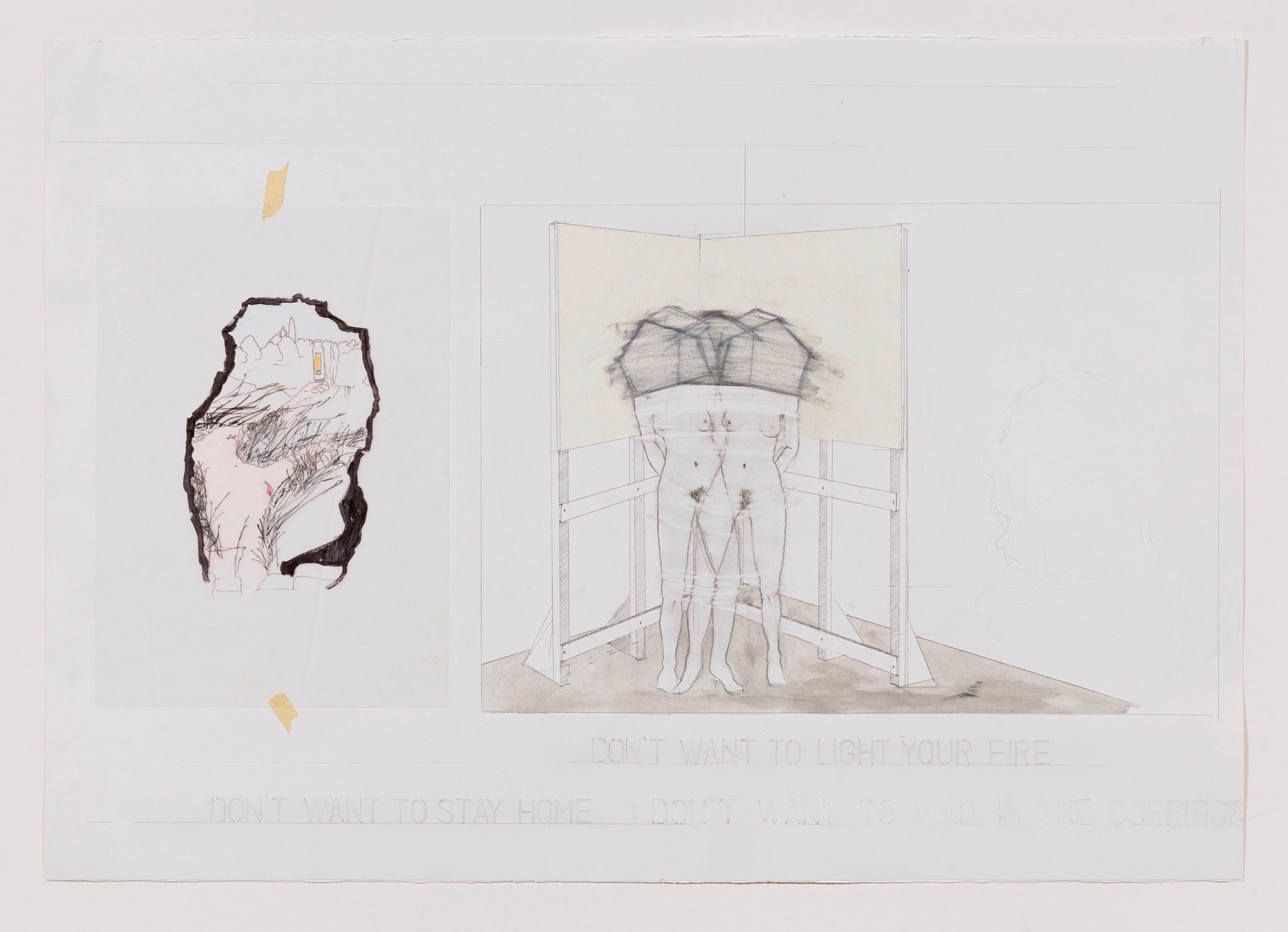

The present works on paper by Monica Bonvicini served as the preparatory sketches for the artist's 1997 video installation Hausfrau Swinging, in which a nude woman wears a prosthetic head in the shape of a house, and bangs it violently against two walls that form a kind of alcove corner, an open yet claustrophobic space that brings to mind and reveals the influence of Bruce Nauman. Bonvicini borrows the imagery of a nude woman with a house for a head from Louise Bourgeois's 1947 drawing, Femme/Maison, another work that shows how architecture can be used to predicate restrictive parameters on gender and identity.

In these works, Bonvicini shows that the structure of the family home is not a neutral or ungendered space. And within this structure, a woman - or, a hausfrau - is identified and meant to identify herself through the prescribed roles of “mother” or “housewife.” However, the violence with which Bonvicini’s hausfrau attempts to break through her house helmet - one that notably obscures her vision but allows her to be seen - is telling of not just the inadequacy of these systems of identification, but also her incapacity, or refusal, to reconcile and assimilate who she is as a subjective individual to who is supposed to be in a given architectural context.

Bonvicini makes further reference to Marcel Duchamp's infamous Etants Donnés, which similarly uses architecture to touch upon issues of voyeurism, violence, fantasy and objectification.

MONICA BONVICINI

Hausfrau Swinging

1997

Color video on monitor, sound, amplifier, speakers, drywall panels, impregnated wood, white paint

205 x 210 x 44,5 cm

Duration: 30’45”

Photo: Jens Ziehe / Courtesy of the artist

"You can avoid people but you can’t avoid architecture."

JAY DeFEO

JAY DeFEO

Untitled

1973

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 5 by 8 in. 12.7 by 20.3 cm.

(MI&N 14727)

JAY DeFEO

Untitled

1973

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 5 by 5 in. 12.7 by 12.7 cm.

(MI&N 14723)

"After completing The Rose and taking a roughly four-year hiatus, Jay DeFeo began to regain her artistic footing again in 1970. She was also retraining her eye to see through the lens of a camera. Much in the same way [André] Breton and his fellow Surrealists prowled the streets and flea markets of Paris on the lookout for objects that exerted a magnetic pull, DeFeo took photographs of shop windows in Larkspur [CA], her new hometown. It was an exercise in Surrealist looking, conscious or not, and she naturally gravitated to those objects that suggested a veiled corporeal form, that same 'enigmatic figurative reference.'

DeFeo gravitated towards subjects that conveyed the vulnerability of the body and her antennae were highly attuned to objects bearing wounds or signs of age. Worn and mottled surfaces have fascinated DeFeo as far back as her European sojourn in the early 1950s."

[Above text by Dana Miller, excerpted from Outrageous Fortune: Jay DeFeo and Surrealism, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2018, pp. 11-13)

JAY DeFEO

White Water

1989

Oil on linen

16 1/8 by 12 in. 41 by 30.5 cm.

(MI&N 12379)

"Jay DeFeo used the idea of man's battles against nature in the way that she had initially with the notion of mountain climbing as a metaphor for her struggles with cancer. Many of the works from this period have references to forces of nature, such as whitewater and mountain climbing. On the eve of her surgery in 1988, she watched a televised climb of Mount Everest. She would use the idea of mountain climbing again as a metaphor for her struggle. This incredibly dynamic composition of White Water [image at right] can be seen in those terms as well."

[Above text by Dana Miller, from a transcript of a tour conducted during Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2013]

"If expressionism implies emotional impact, I can realize it only by restraint and ultimate refinement."

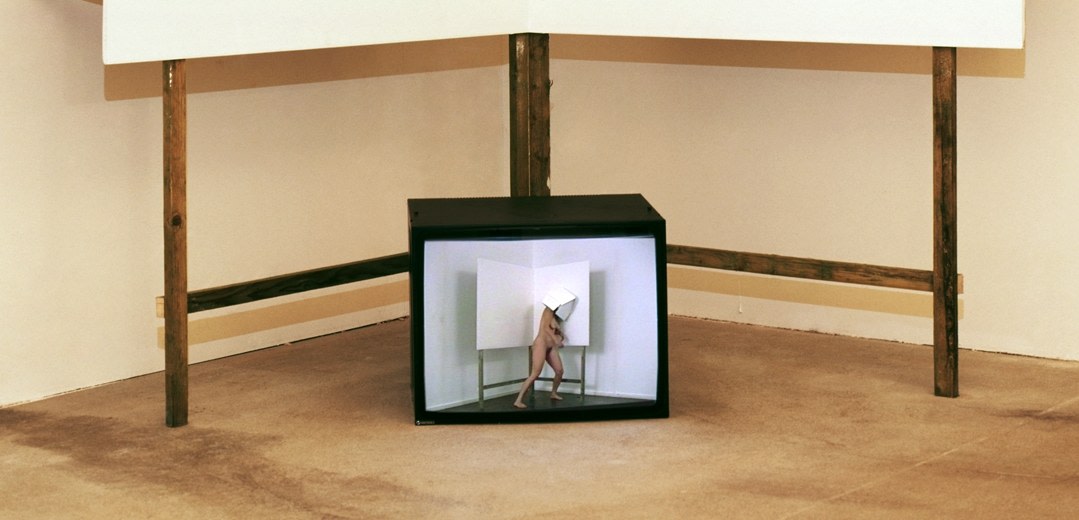

NANCY GRAVES

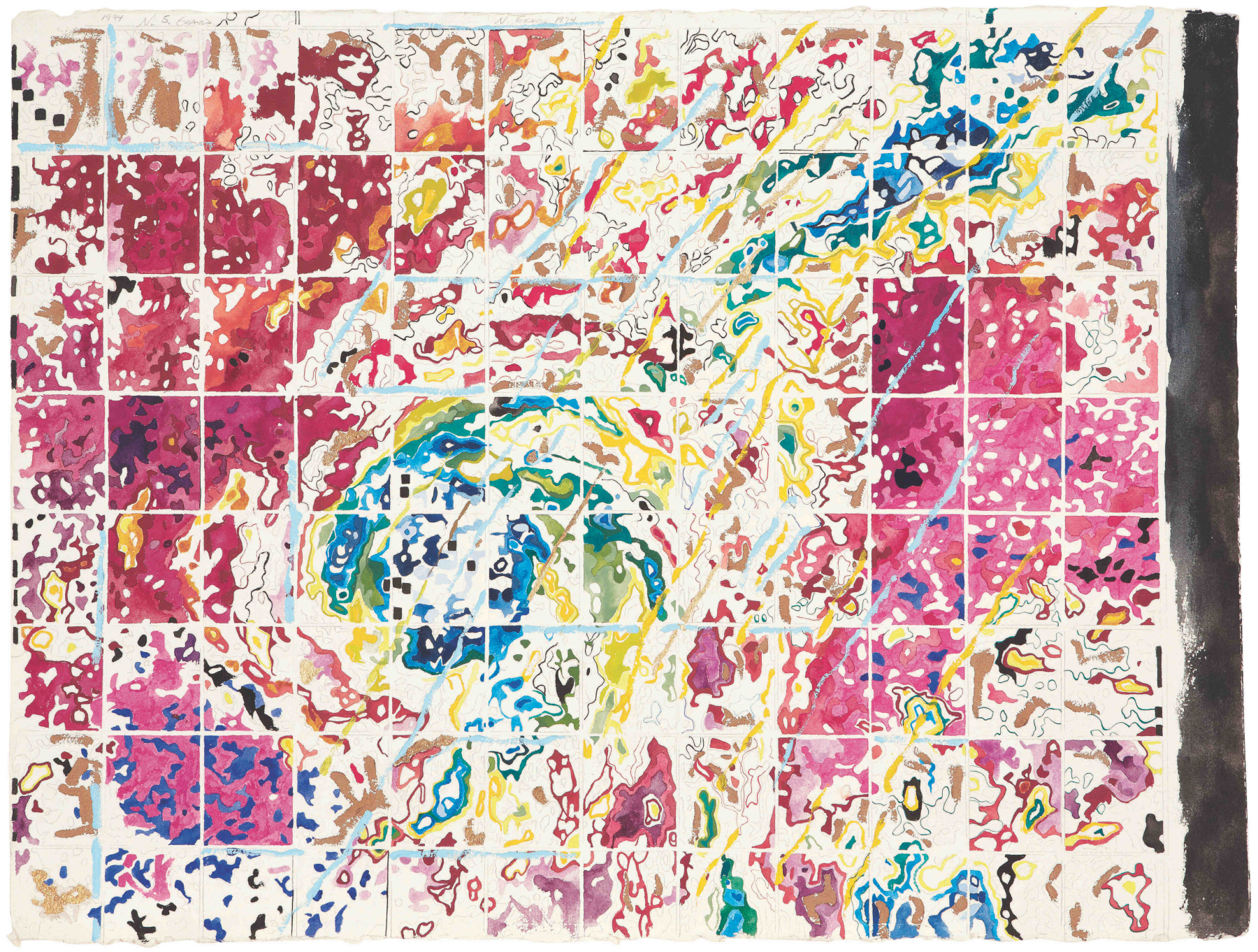

NANCY GRAVES

First Look at the World's Weather

1973

Acrylic, India ink and gouache on paper

22 1/2 by 60 in. 57.2 by 152.4 cm.

Signed and dated "73"

(MI&N 15106)

NANCY GRAVES

Untitled (Heat Density Measurement of a Cyclone)

1974

Watercolor, gold leaf and graphite on paper

22 1/2 by 30 in. 57.2 by 76.2 cm.

Signed and dated 1974

(MI&N 15116)

During the 1970s, Nancy Graves made a substantial body of paintings, drawings, prints and a film that delved into the systems that underlie the production and legibility of maps. While her earliest works were based on illustrations selected from ethnographic studies of Polynesian and Inuit navigational maps, Graves’s formal engagement with mapping took a new direction when she chose to depict detailed images of the topographies of Mars, the Moon, Mercury and Earth’s ocean floors based on data transmitted by orbiting satellites, then a pioneering technology.

The above work, First Look at the World's Weather, is based on a global photomosaic that was assembled from 450 individual pictures taken by the satellite Tirox IX on February 13, 1965. The horizontal white line marks the equator. Special photographic processing was used to increase the contrast between major land areas, outlined in white, and the surrounding oceans. The brightest features on the photographs are clouds; ice in the antarctic and snow in the north are also very bright. The clouds are associated with many different types of weather patterns. The scalloping at the bottom shows how the earth’s horizon appears in individual pictures.

“You can’t call it landscape imagery, you’ve got to be at least three hundred miles out in space - looking down... It’s by a machine that has a lens that can record, so that in itself is kind of marvelous. This is a concept from which I’m working about form-making, vis-a-vis technology.”

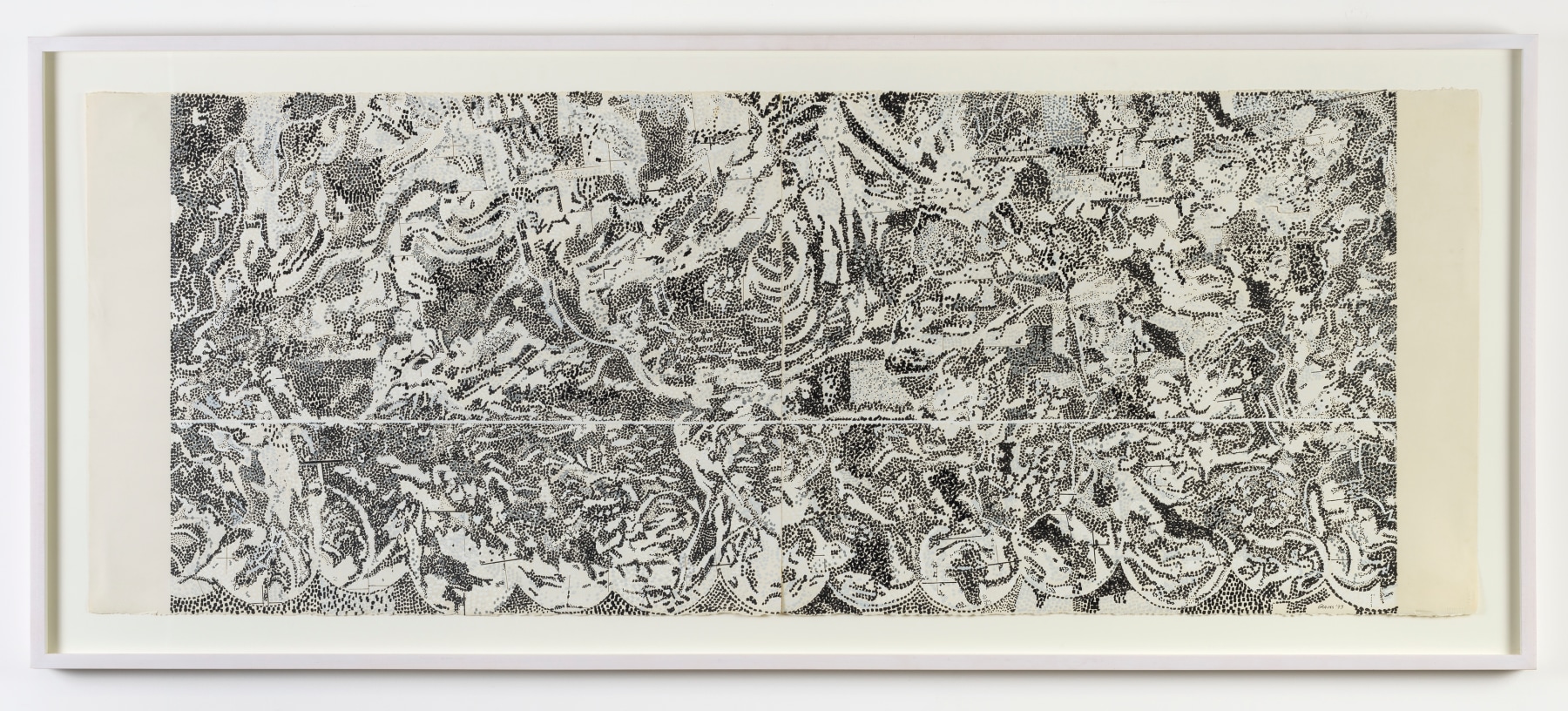

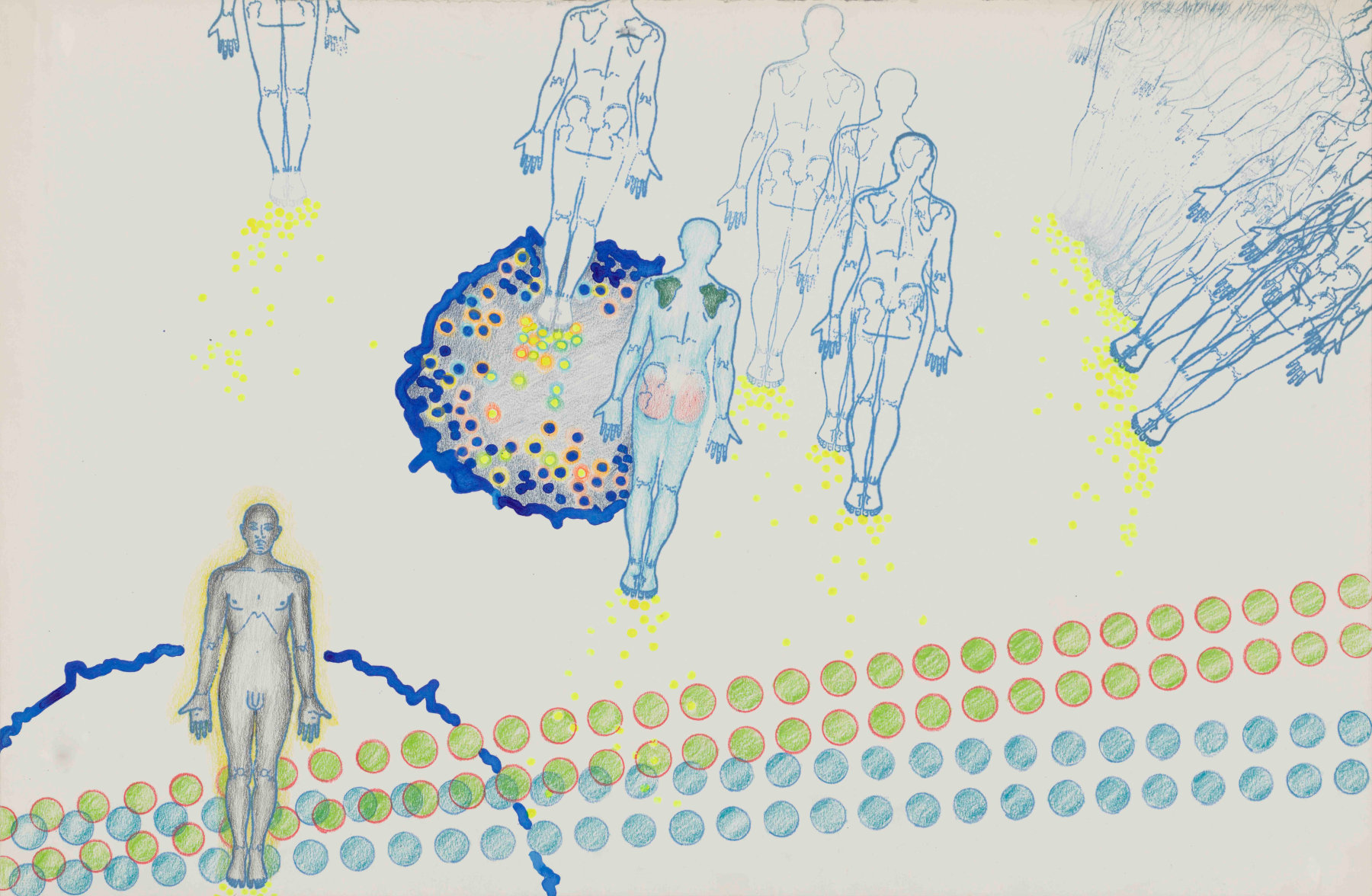

KIKI KOGELNIK

KIKI KOGELNIK

Untitled (Robots)

c. 1967

Acrylic, color pencil and ink on paper

15 by 23 in. 38.1 by 58.4 cm.

(MI&N 15824)

MARCEL DUCHAMP

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915-1923)

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952)

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

"For Kiki Kogelnik, the human body was something that could be engineered, programmed, plugged in and turned on. Parts could be swapped out and mechanical prostheses added. Her exploration of bionic pesonages surfaces in several rudimentary ink drawings, [like the work titled Untitled (Robot) (1964), shown below]. The body cavity in this work resembles a boiler room or car engine more than human anatomy.

Kogelnik's technoid appendages and bionic bodies recall the 'mechanomorphology' of Marcel Duchamp's Coffee Grinder (1914) and other components of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915-23), as well as Francis Picabia's mechanomorphs.

Besides the human figure, the circle was the most frequently employed motif in Kogelnik's visual vocabulary [as shown in the above work Untitled (Robots) (1967)]. She used various methods of creating level circles in her paintings and works on paper: stencils, stamps, hole punches and tracing objects. Kogelnik often used the circle motif to convey a sense of transparency, creating overlapping images or perforating her forms. The effect of this totalizing device is to remind us that the entirety of our universe is composed of the same basic elements; in essence, we are all made of stardust."

[Above text by Dana Miller, excerpted from "Leaving an Impression: The Art of Kiki Kogelnik," Kiki Kogelnik, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2019, pp. 10-12]

"I am involved in the technical beauty of rockets, people flying in space and people becoming robots."

JUSTINE KURLAND

JUSTINE KURLAND

Orchard

1998

Digital pigment print, AP1/2 from the ed. of 6 plus 2 AP

30 by 40 in. 76.2 by 101.6 cm.

(MI&N 15066)

SIR JOHN EVERETT MILLAIS

Apple Blossoms (c. 1856/59)

Collection Lady Lever Art Gallery, United Kingdom (Wikimedia Commons)

"Moments serene enough to be from a Claude Lorrain, staged beneath a freeway overpass or on the banks of a toxic swamp. Pastoral bathers wear concert-tour T-shirts; highway angels with dirty fingernails shoplift Oreos; Pre-Raphaelite nymphs capture hapless boys who’ve happened on the wrong glade. Each of Justine Kurland’s photographs is a vignette from an ongoing narrative. Inspired by autobiography no less than by fairy tales, movies, Afterschool Specials, even painting in the Grand Manner, Justine’s World is an idyll where fact melts into fiction, where every girl is beautiful and your friends always look out for you."

[Above text by Meghan Dailey, "1000 Words: Justine Kurland," Artforum, April 2000, p. 114]

"I’m always thinking about painting: nineteenth-century English picturesque landscapes and the utopian ideal, genre paintings, and also Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs. I started going to museums at an early age, but my imagery is equally influenced by illustrations from the fairy tales I read as a child."

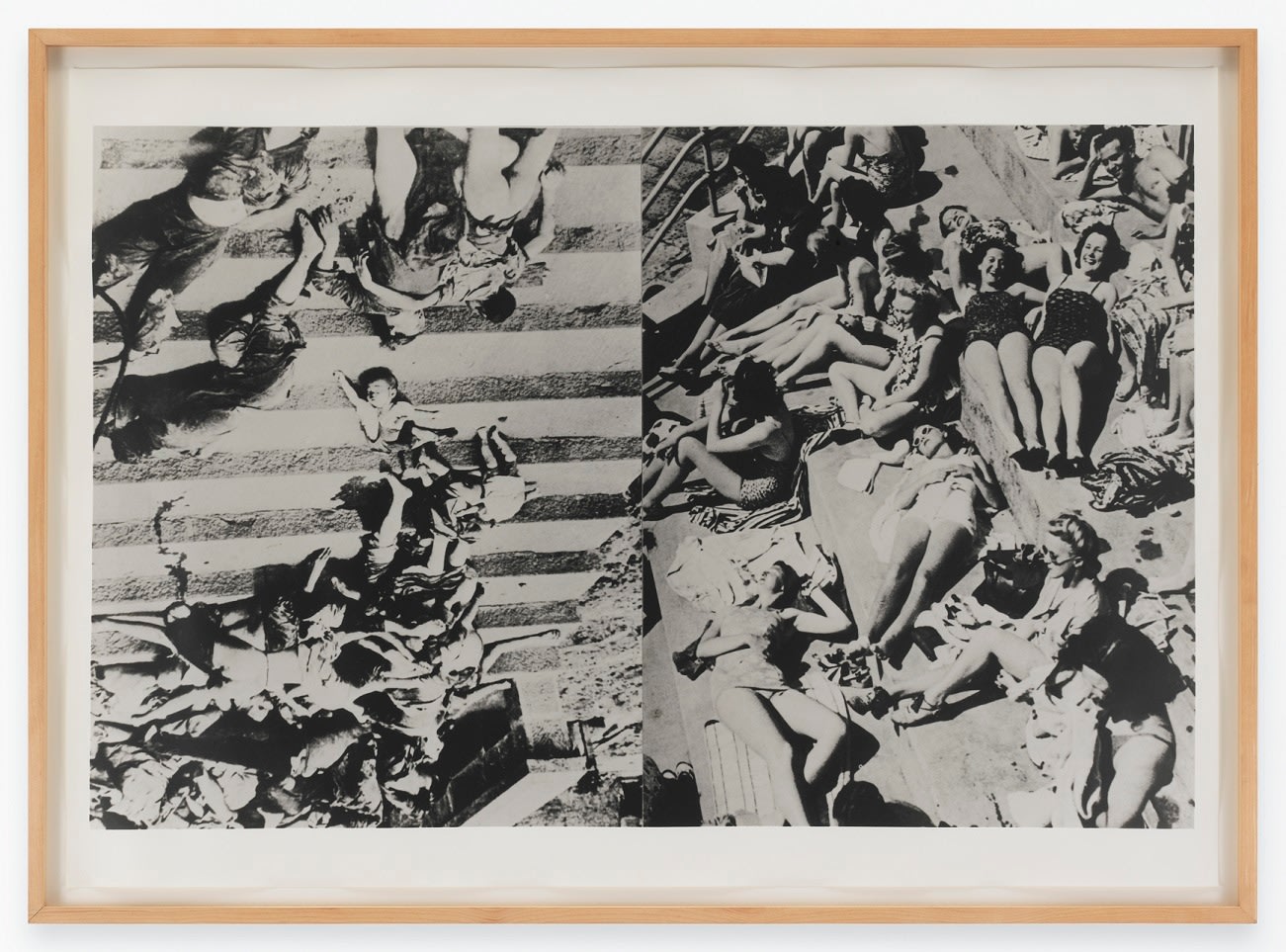

ANNETTE LEMIEUX

ANNETTE LEMIEUX

Mon Amour

1987

Gelatin Silver, AP1/1 from the edition of 3 plus 1 AP

35 by 50 in. 88.9 by 127 cm.

(MI&N 15372)

ALAIN RESNAIS

Hiroshima mon amour (Pathé Films, 1959)

Screenplay by Marguerite Duras

For more than 30 years, Annette Lemieux has produced a conceptually informed body of work which challenges traditional notions of visual style. Part of a generation of artists who emerged around the time of Douglas Crimp’s hugely influential Pictures exhibition in 1977, which applied the word “pictures” to artworks to defy medium specificity, her work takes its point of departure in a radical questioning of aesthetic hierarchies. Using a variety of techniques as well as media, including painting, photography, sculpture, collage and a combination of the above, she addresses socially pertinent topics such as history, war and identity.

The above work, titled Mon Amour, combines two disparate images: one shows the devastating aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima; the other is a candid tableau of an American holiday locale. Both images were taken from Time-Life photography books and, while vastly contrasting in subject matter, they are linked visually through the shared elevated perspective and the motif of the staircase. The work shows how two very different situations - one horrific and one not - could exist at the same time. Through the title, the artist references French filmmaker Alain Resnais's 1959 film Hiroshima mon amour (screenplay by Margeurite Duras), wherein a French actress and a Japanese architect contemplate the impact of the atomic bombings across a nonlinear storyline that conflates and confuses past, present and future.

ANNETTE LEMIEUX

Wound

1991

Head form with oil paint and metal stand

13 1/4 by 6 1/8 by 7 1/2 in. 33.7 by 15.6 by 19.1 cm.

(MI&N 15376)

The sculpture at left is inspired by the Philip Guston painting Head (1977) in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The work depicts a sutured head wound, which underlies the fragility of a life at stake and the crudeness of medical necessity. Wound's head form is based on the measurements of the artist's own head and, with the accompanying pedestal, stands at her height, and represents an effort to bandage the wound, figuratively and literally. There are four different archetypes in this series: Redverbot (1991), Speak (1992) and Hearing Thing (2013).

"Found and assisted ready-made objects have the ability to lead viewers into the space of the work and offer a familiar way to start a dialogue with it. When I painted, it was geometric. When I wanted to allude to a place or a person, it was photographic."

JESSICA STOCKHOLDER

JESSICA STOCKHOLDER

[JS 123]

1990

2 by 4 hinged to wall with papier mache, photo, and paint

Height: 24 in. 61 cm.

(MI&N 10003)

Jessica Stockholder is known for her idiosyncratic, charged constructions that simultaneously occupy the fields of painting, sculpture and architecture. Since the 1980s, she has combined readymade and manipulated objects into at once simple and complex, formal and chaotic works that challenge conventional understandings of the separation between pictorial and actual space. Through her choice of everyday materials—including rugs, grocery store shopping baskets, wires, printers, real and artificial fruit, lamps, driveway mirrors and plastic bumps used for foot massage—her assemblages are suggestive of surrealist narratives, while also emerging as abstract tableaux in which color, texture and the space in between assume autonomy.

"My work is sculptural. It uses things in the world. It’s concerned with weight and mass and space, but it’s organized by painting conventions in large part."